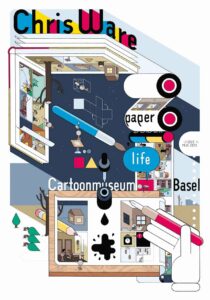

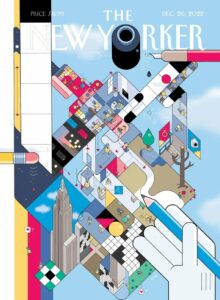

Uma boa entrevista com o autor de Building Stories ilustrada com um autorretrato do autor – hoje em dia e a versão adolescente muito doida.

What advice would you give to someone who is in the early stages of that and possibly struggling?

To work as hard as possible, and then, when you think you’re done, to work just a little bit harder. To know that if it feels “right” it may actually be completely wrong, and that if it feels “wrong” it may be completely right. There’s no governing principle to any of this except that strange instinct and feeling within yourself that you simply have to learn to trust, but which is always unreliably changing. To create something for people who have not been born yet. To pay attention to how it actually feels to be alive, to the lies you tell yourself and others. Not to overreach—but also not to get too comfortable with your own work. To avoid giving in to either self-doubt or self-confidence, depending on your leaning, and especially to resist giving over your opinion of yourself to others—which means not to seek fame or recognition, which can restrain rather than open your possibility for artistic development. With all this in mind, not to expect anything and to be grateful for any true, non-exploitative opportunity that presents itself, however modest. And to understand that being able to say “I don’t know what to do with my life” is an incredible privilege that 99% of the rest of the world will never enjoy.

There’s a quotation from Picasso on the inside cover of Building Stories: “Everything you can imagine is real.” You said at Unity Temple that you can remember stories your grandmother told you and how they looked in your head more vividly than some events that actually occurred in your own life. There’s that part in one of the Building Stories booklets where one of the characters dreams that she finds an amazing book she wrote, and even though it only ever existed in her subconscious, it confirmed for her that she had that potential in her. I’d never considered giving so much validity to a reality that’s so personal and in-your-head and fictionalized, and I found it very comforting. So, how did you figure that out on your own—that something that exists only in your mind could have a valid enough reality to be a comfort?

Well, really, our memories are all we have, and even those we think of as “real” are made up. Art can condense experience into something greater than reality, and it can also give us permission to do or think certain things that otherwise we’ve avoided or felt ashamed of. The imagination is where reality lives; it’s the instant lie of backwash from the prow of that boat that we think of as cutting the present moment, everything following it becoming less and less “factual” but no less real than what we think of as having actually occurred.

Normally your books are quite carefully put together, and reading them can be like solving a maze—the order and arrangement of the panels is very purposeful and important.Building Stories is a box of books and pamphlets and broadsides and the like, but you’ve set no guidelines for where to start or finish. Why?

I wanted to make a book that had no beginning or end, and, despite the incredible pretentiousness of how that sounds, to try and get at the three-dimensionality of memories and stories—how we’re able to tell them starting at this or that point depending on the circumstance, and to take them apart and put them back together, whether to actually try and make sense of our lives or simply to tell reassuring lies to ourselves. I also wanted to make a book that seemed fun to read, and the idea of a box of nonthreatening booklets has always appealed to me. Also, I had a dream about exactly such an object.

O resto tá aqui.